Building an LLM From Scratch: The Full Story

The Person Behind It

Enterprise Cloud Architect by day. Not an ML researcher. Not a PhD student. My day job doesn't involve creating LLMs — nobody was ever going to task me with this. I didn't go to university for machine learning, but my life experiences taught me how to learn. So I went and learned, like I have been doing my entire life. I didn't wait for anyone to give me permission.

The drive was simple: I want to make an LLM that is useful, myself, from scratch. Not fine-tune someone else's model. Not call an API. Build the whole thing. But I realized quickly I can't compete with general-purpose models — not with my resources, not with anyone's resources short of a hyperscaler. So I settled on a domain-specific small language model. I thought a lot about what domain, and chose World War II because the facts are mostly unchanging, and because Wikipedia as well as the U.S. government have a lot of freely available materials on the topic.

So I took to it outside of work — during personal time, using personal resources and personal dollars — in the place where I call the shots. In the place where I am the ruler of my time. This is blocker resolution. Not letting anything stop me.

The first commit landed at 8:45 PM on September 15, 2025: "initial license and readme." By midnight there were Terraform configs deploying spot instances on AWS. The infrastructure guy built infrastructure first — of course he did.

Then silence. Another personal project took two months of my time. I completed it, and came back to building my own LLM — this time with something much bigger than cloud infra in mind.

711 Commits. 5 Months. One GPU.

The Machine: A single NVIDIA RTX 4070 Ti Super with 16GB of VRAM. Consumer hardware. The kind of card you'd buy to play games on. Every architectural decision, every hyperparameter choice, every engineering workaround in this project exists because of that 16GB constraint.

The Corpus: 301 curated Wikipedia articles about World War II. Raw, that's roughly 40 megabytes of text. For a language model, that's almost nothing — nowhere near enough for a model to learn both English and domain knowledge. Corpora is the primary bottleneck of LLM training. This is the central problem the entire project had to solve.

The Synthetic Data Factory: 40MB Becomes 5.2GB

The solution was building a synthetic data generation pipeline. Using Qwen 2.5 7B (and later Qwen 3) as a tool — not a knowledge source — the pipeline transforms those 301 articles into over 1.25 million training records across dozens of question-answer styles and formats.

The purpose is threefold:

- Teach the model WWII content from the source material

- Teach the model English language patterns and task completion, without straying outside the WWII domain

- Overcome the tiny corpus — 40MB of source text became 5.2GB of training data

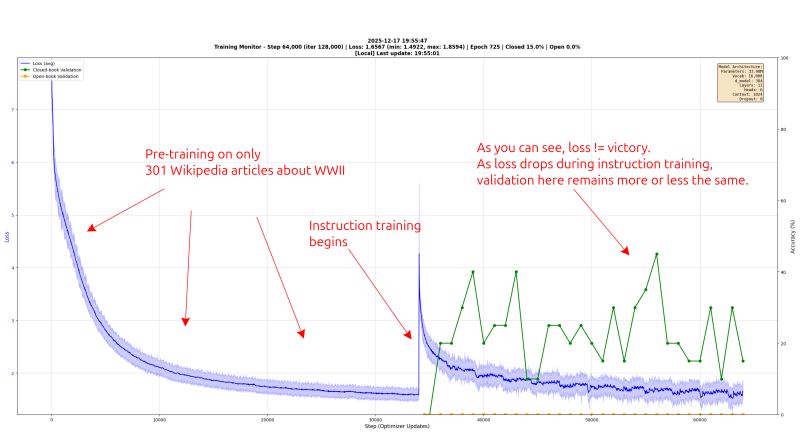

But there was a trap. Training exclusively on QA pairs — even 1.25 million of them — built a Jeopardy bot, not a historian. Ask it a question and it would answer. Give it a topic and it had nothing to say. It could respond but it couldn't talk. The model had no concept of continuous prose, no sense of narrative or exposition. The first attempt at a fix was the traditional two-phase approach: feed the model raw Wikipedia text first — Continued Pre-Training — so it learns what English prose sounds like, then layer in the QA pairs as Supervised Fine-Tuning. But that had its own problems. Loss would drop beautifully during instruction tuning, but validation scores stayed flat. Low loss doesn't mean the model is actually answering questions well — it means the model is good at predicting the next token in its training format. The loss curve was lying.

The real breakthrough was Q-PT — Question Pre-Training. Instead of feeding the model raw Wikipedia text and hoping it absorbs knowledge through next-token prediction, Q-PT wraps that same raw text in ChatML format with diverse, realistic user questions. "What happened at Stalingrad?" gets the original Wikipedia passage as its answer. "Tell me about the Eastern Front" gets the same passage. Twenty-eight different question phrasings per text chunk — formal, casual, with typos, imperative, conversational — all with the raw text as the answer, and loss masking so the model only trains on the answer portion. The model learns to answer questions from its very first forward pass. No behavioral shift needed later. No "unlearning" continuation behavior. Q&A is its first language.

The diversity matters. The model sees the same WW2 facts through 70+ different question styles per text snippet: who/what/when/where/why, true/false statements, adversarial wrong-entity questions, fill-in-the-blank, multiple choice, academic rephrasing, journalistic rephrasing, chronological restructuring, and on and on. This teaches the model a wide range of English patterns, all grounded in verified source material. Fundamentally different from training on noisy internet text full of inaccuracies.

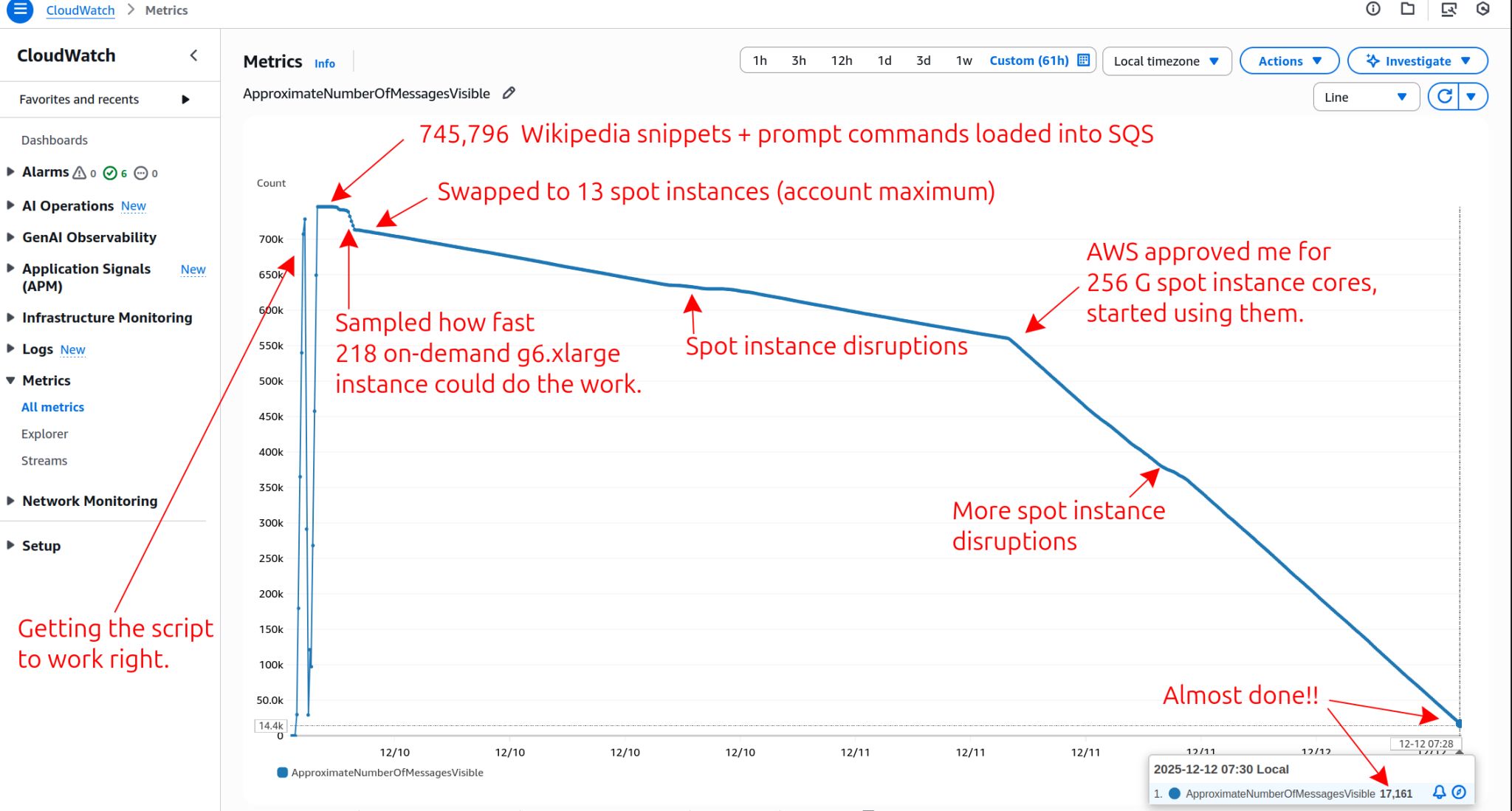

The generation process works on 8-sentence snippets with a sliding window of 4 sentences. Each snippet generates QA pairs across all applicable prompt types. One generation job took over 800 hours on the RTX 4070 Ti Super — that's over a month of continuous GPU time for a single workload. By the time it finished, I had halfway forgotten how my own project was structured and how things worked. It took a few hours of re-reading my own code to get back up to speed. And that was just one run. Five-day and ten-day generation runs are routine. Twenty-four-hour one-offs are common — spin up a specific prompt type, let it grind through every 8-sentence snippet overnight, wake up to new training data. This is a project measured in weeks and months, not hours.

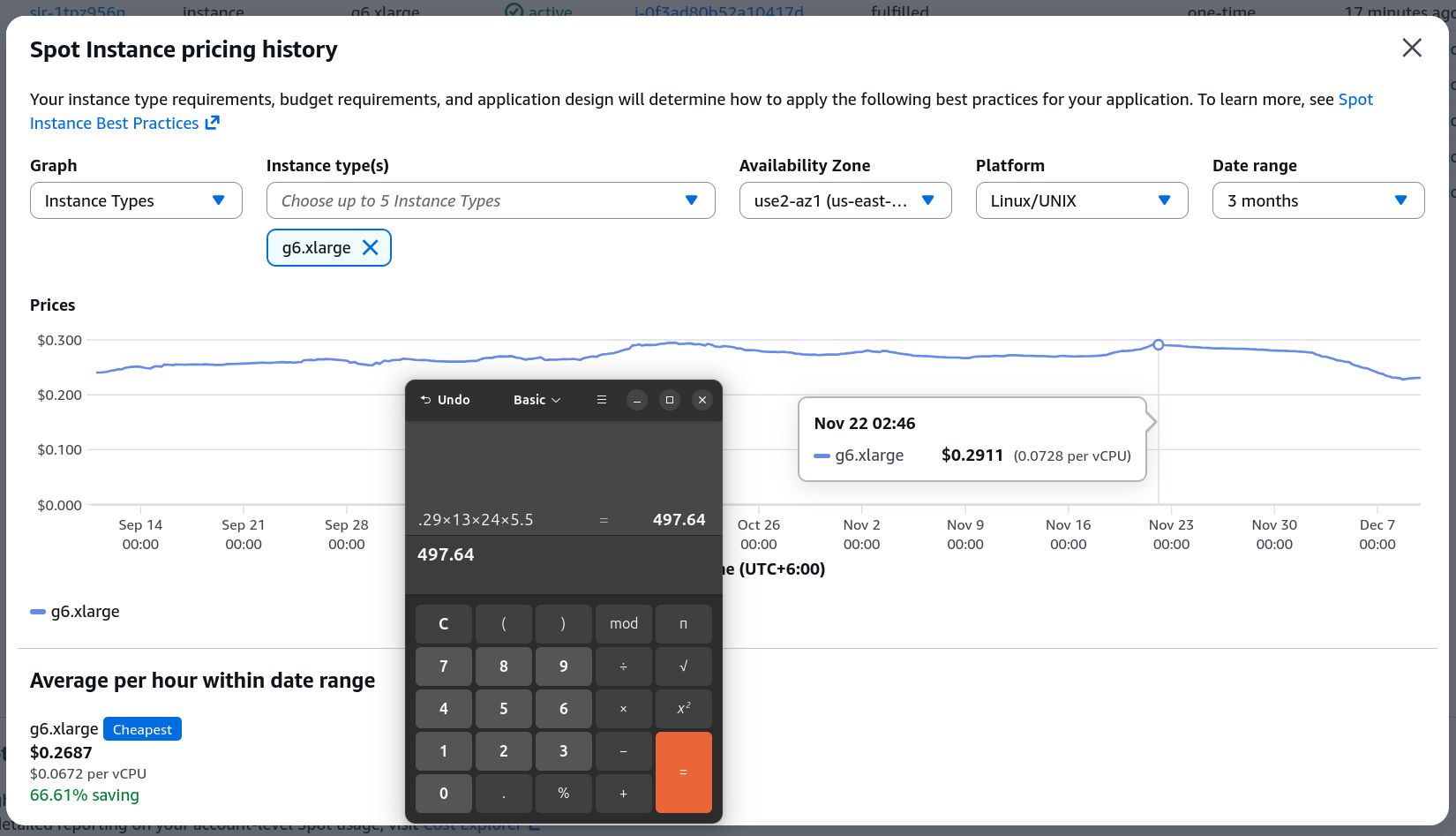

A fault-tolerant distributed pipeline was also built in AWS — SQS queues feeding hundreds of parallel Qwen instances running on g6 spot instances, with S3 as the durable store. The infra guy's instincts kicking in. Each instance pulls work items from the queue, processes sliding-window snippets through Qwen, and writes results to S3. When AWS reclaims a spot instance mid-generation — and they do — the work item returns to the queue and another instance picks it up. No data lost. The system scaled horizontally and ran unattended.

It was very efficient, but still cost real dollars, and that's expensive for what amounts to a hobby. So I bought a video card and built a tower to put it in. One-time cost for endless usage. The RTX 4070 Ti Super is low-end for this work — things take a while, and I'm limited to fairly small helper LLMs like Qwen 3 4B — but Qwen 3 4B is extremely capable. I could not have done all this without Qwen.

The GPU just runs. It hasn't stopped. This is one of the golden rules I've set for myself concerning owning expensive GPUs: never let them rest. Always be doing something with them. Always have work lined up. Never sitting idle. LLM quality for someone like me — someone who can't buy corpora, who uses free knowledge sources like Wikipedia — depends on synthetic data. So the rule is to endlessly generate synthetic data. You can stop, reprioritize one type of data over another, but the key is to keep the machine working 24/7 so that in the future you can build better models, or even select what data you want to include in a future model.

The Tokenizer Wars: 8K, 16K, 32K

A custom SentencePiece tokenizer trained on the WWII source data. Vocabulary size went through extensive iteration:

- 8K vocabulary — the model stalled out. Not enough resolution.

- 16K vocabulary — also stalled.

- 32K vocabulary — resolved the stalling. The current tokenizer.

Deliberate decisions were made about token granularity. All years relevant to WWII are encoded as single tokens — "1944" is one token, not "19" + "44". All 12 months are single tokens. This forces the model to treat dates as atomic concepts rather than composing them from subword pieces. Military terms like "Wehrmacht," "Luftwaffe," and "Messerschmitt" each compress to a single token. The result: ~40% fewer tokens per text compared to 16K vocabulary.

The Architecture: A Custom GPT-2 From Scratch

Not HuggingFace. Not a wrapper around someone else's model. A custom GPT class written from scratch, loaded from raw checkpoints. No AutoModelForCausalLM anywhere.

Current architecture:

- 18 transformer layers, 768 embedding width, 12 attention heads

- 4096 token context length

- 32,000 token vocabulary

- ~183M parameters

Every dimension was chosen empirically:

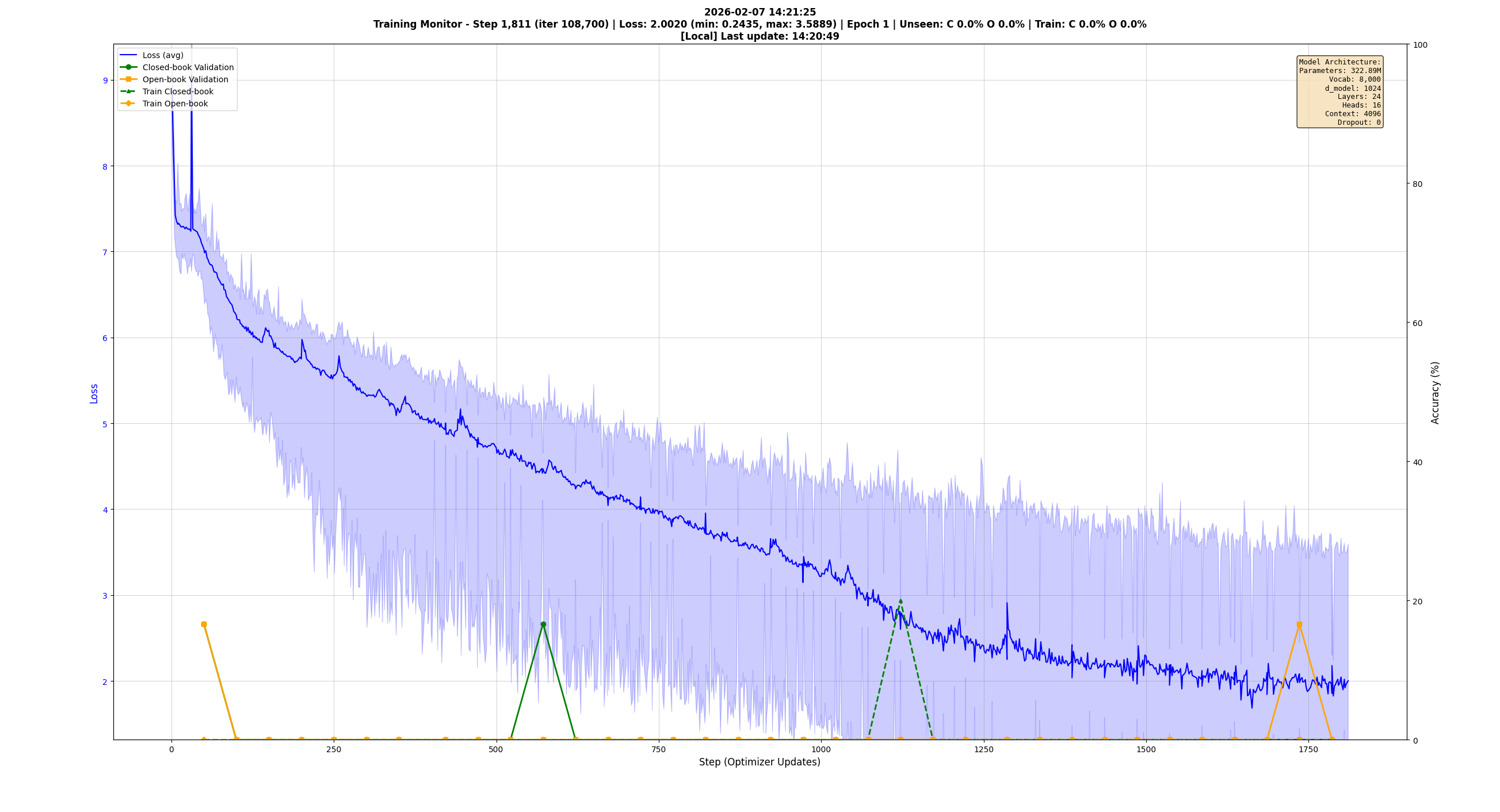

Why 183M: The largest model that trains with a physical batch size of 3 on the 4070 Ti Super while leaving ~1GB of VRAM free — enough to run Firefox, watch YouTube, and browse LinkedIn during training runs. Smaller models weren't adequately absorbing the information. The exported model archive tells the story of sizing experiments: starting at 33M, growing to 54M, 71M, 73M, 185M — each one tested, many of them failures with honest names. I even tried 322M — my biggest attempt. It took a long, long time to train. I was seeing if size would solve my problems. It didn't. I had data problems, not size problems.

Why 4096 context: Fit as much information as possible into each training context for better model quality, without creating hardware pressure.

Why 12 attention heads: Each head can latch onto different details and features. Research shows even a single head can handle multiple features, but 12 provides granularity for specialized attention patterns.

Why zero dropout: At this small model scale and data density, dropout prevented fact absorption. The model needs to memorize specific facts about WWII — Wehrmacht commanders, battle dates, casualty figures — and dropout worked against that goal.

ChatML: Teaching the Model When to Shut Up

The model uses ChatML formatting with special token encoding. Each ChatML tag is exactly one token. The model needs to know unambiguously when to stop generating, and single-token boundaries make that a clean, learnable signal.

This sounds simple. It wasn't.

One commit from January 31 tells the story: "correct <|im_end|> masking so model trains on it." The loss mask was accidentally excluding the end-of-message token from training. The model literally could never learn when to stop talking. One boolean mask, one line of code, weeks of mysterious behavior.

And then there was the Chinese output problem. I speak English, so I want an English-only model. Qwen is a Chinese model. It's incredible at English, but sometimes it slips — especially at higher temperatures or with ambiguous prompts. When you're generating over a million training records, "sometimes" means thousands of contaminated outputs if you're not careful.

So every single piece of generated text — every question, every answer, every clarification, every rephrased passage — passes through two defensive checks before it's accepted.

First, the lingua library. I build a language detector tuned for English and Chinese, and I require 100% English confidence. Not 99%. Not 0.98. The full 1.0. Anything less and the item is rejected with a tagged failure reason so I can see exactly which phase failed and why.

Second, a raw Unicode range scan. I check every character in the output against the CJK Unified Ideographs block — U+4E00 through U+9FFF. If even a single Chinese character made it through, the item is dead. This catches things the language detector might miss — like a single hanzi tucked inside an otherwise English sentence that lingua might still score at 1.0 confidence.

Both checks. Every phase. Every volley. No exceptions. If the question is clean but the answer has one Chinese character, the whole item goes to the failed directory. This is how I ensured I was creating an English speaking model.

The Batch Size Wars: November 30, 2025

One single day, 50+ commits. Each one a batch size change:

try 16 → try 20 → try 18 → 16 it is → 12 → 14 →

28 → 24 → 26 → 25 → 24 → 23 →

50 → 75 → 64 → 70 → 68This is the reality of training on consumer hardware. Too large and CUDA OOM kills the process. Too small and training takes forever. The final answer: physical batch size of 3, with gradient accumulation bringing the effective batch size to 120.

Context Packing: The Attention Bleed-Over Crisis

Early training packed multiple QA pairs into each 4096-token context for efficiency. This caused attention bleed-over — tokens from one QA pair were attending to tokens from an adjacent QA pair within the same packed context. The model was learning cross-contaminated relationships between unrelated sequences.

The first fix was training with individual QA pairs, one per context. This eliminated bleed-over but was extremely slow — most of each 4096-token context was padding tokens.

The real solution was diagonal attention masking. This packs multiple QA pairs into a single context while using Flash Attention 2 to create block-diagonal attention masks. Each packed sequence gets its own isolated attention window within the same context — full utilization, zero cross-contamination.

But the first implementation didn't correctly use Flash Attention 2, causing performance slowdowns. Once corrected, training speed improved significantly.

And then the off-by-one. During context packing, document IDs and position IDs were being shifted for target alignment — a token from one packed sequence was slipping into the attention mask of the adjacent sequence. Debugging attention masks at the token level. The fix was surgical: one line changed, ten lines deleted.

Here's the thing nobody tells you about context packing: it completely changes your batch math. Remember the Batch Size Wars — physical batch size of 3, gradient accumulation to an effective batch size of 120? That's 120 contexts per optimizer step. But each 4096-token context now packs 15 to 30 independent QA pairs. That means each optimizer step processes roughly 1,800 to 3,600 independent training examples — not 120. Hyperscaler-level batching on a consumer GPU. Context packing didn't just fix the padding waste problem. It accidentally gave the model a massive effective batch size that would otherwise be impossible at this hardware tier.

Loss Flapping: The Shuffling Problem

Early data shuffling was done by shuffling chunks when producing training files. Because the data was originally organized by article, information was still bunched together even after shuffling. This caused loss to flap — the model would see clusters of related information, then clusters of different information, and the loss would oscillate instead of converging.

The fix was old-school sharded shuffling — a file-based shuffling technique that distributes every record randomly across 1,000 shard files. Uses almost no system RAM, because system RAM was also a bottleneck. The full dataset is too large to shuffle in memory. Sharded shuffling solved both the loss flapping and the RAM problem simultaneously.

VRAM Management: The Orchestrator

Running both training and validation requires loading different models — the training model and a Qwen judge LLM for evaluation. Both cannot fit in 16GB VRAM simultaneously.

Early attempts tried unloading the training model to load the judge, then reversing. This led to OOM errors — PyTorch's CUDA memory allocator doesn't fully free VRAM when you delete a model. The commit messages tell the story of increasingly desperate attempts: "aggressively clean memory after validation completes." "unload llama." "aggressively clear vram." None of it worked reliably.

The solution was an orchestration script that completely terminates one process before starting the other. Training and validation run as separate programs. The orchestrator kills one to start the other. No shared process state. No model unloading. The OS reclaims all VRAM when the process dies. Elegant in its brutality.

Weight Decay: The Two-Phase Schedule

Training runs hard for 2 epochs with weight decay at 0.1 (the GPT-2/GPT-3 industry standard), then weight decay is lowered to 0.05. The reduction allows more fact absorption in later training, loosening the regularization pressure once the model has learned general patterns.

Contrastive QA: Fighting Positional Bias

Small language models suffer from semantic drift — the embedding space is compressed enough that vectors for related but opposite concepts sit dangerously close together. "Increase" and "decrease." "Before" and "after." "Cause" and "effect." The model doesn't confuse random things — it confuses similar things. Ask it when the Spanish Civil War started and it might say 1917, because it grabbed the strongest "revolution" vector it could find. The dates, the people, the events — they blur together at this scale.

One specific challenge was detail ambiguity — the model blurring similar facts together. "Who commanded the 6th Army?" could get confused with "Who commanded the Afrika Korps?" The solution was contrastive QA pairs for every single detail extracted from the wiki articles.

An entire sub-pipeline handles this. First, Qwen extracts features — people, places, events, dates, numbers — from every article. Then for each feature, a binary-choice question is generated:

Q: Who commanded the 6th Army at Stalingrad, Paulus or Rommel?

A: Paulus commanded the 6th Army at Stalingrad.But here's the problem: Qwen naturally places the correct answer first 60-80% of the time. The model learns "always pick first option" instead of actually discriminating. Prompt engineering can't reliably overcome this.

The solution: don't fight the bias. Generate both orderings. A swapping pipeline creates the inverse:

Q: Who commanded the 6th Army at Stalingrad, Rommel or Paulus?

A: Paulus commanded the 6th Army at Stalingrad. (same answer, different position)Mix both datasets. 50/50 positional distribution. The model learns to discriminate, not memorize position. Over 215,000 contrastive pairs in the final dataset — and this is still being refined.

Single-Prompt vs. Prompt-Chaining

A recent discovery: single-prompt QA generation is far superior to generating questions and answers separately, at least with Qwen 3 4B. Generating both the question and answer in one call produces better results than prompt-chaining — generating a question first, then in a separate call generating an answer. The model benefits from seeing the full task in one shot.

The Honest Graveyard: 25 Exported Models

The model archive contains 25 exported snapshots. Their names tell the real story:

WWII-33M-base <- The beginning

wwII-base-54M <- A little bigger

ww2_71M_instruct_trained_not_good <- Honest

ww2_71B_instruct_trained_106k_steps_and_sucks <- 106K steps. Still sucks.

ww2_73M_8k_vocab_collapsed <- Model collapsed during training

ww2_73M_instruct_trained_broken <- Broken

ww2_185M_dirty <- Not clean

ww2_179M_vocab_32k_loss_1.59_step_6975 <- Getting somewhereEach one represents days of GPU time and the willingness to label a failure clearly and move on. One commit captures the mood: "long sigh." Another: "more corrections that probably don't work." And: "8 bit I guess."

Where It Stands Now

The current model — 183M parameters, 32K vocabulary, 4096 context — is the best one yet. And I'm immensely proud of this.

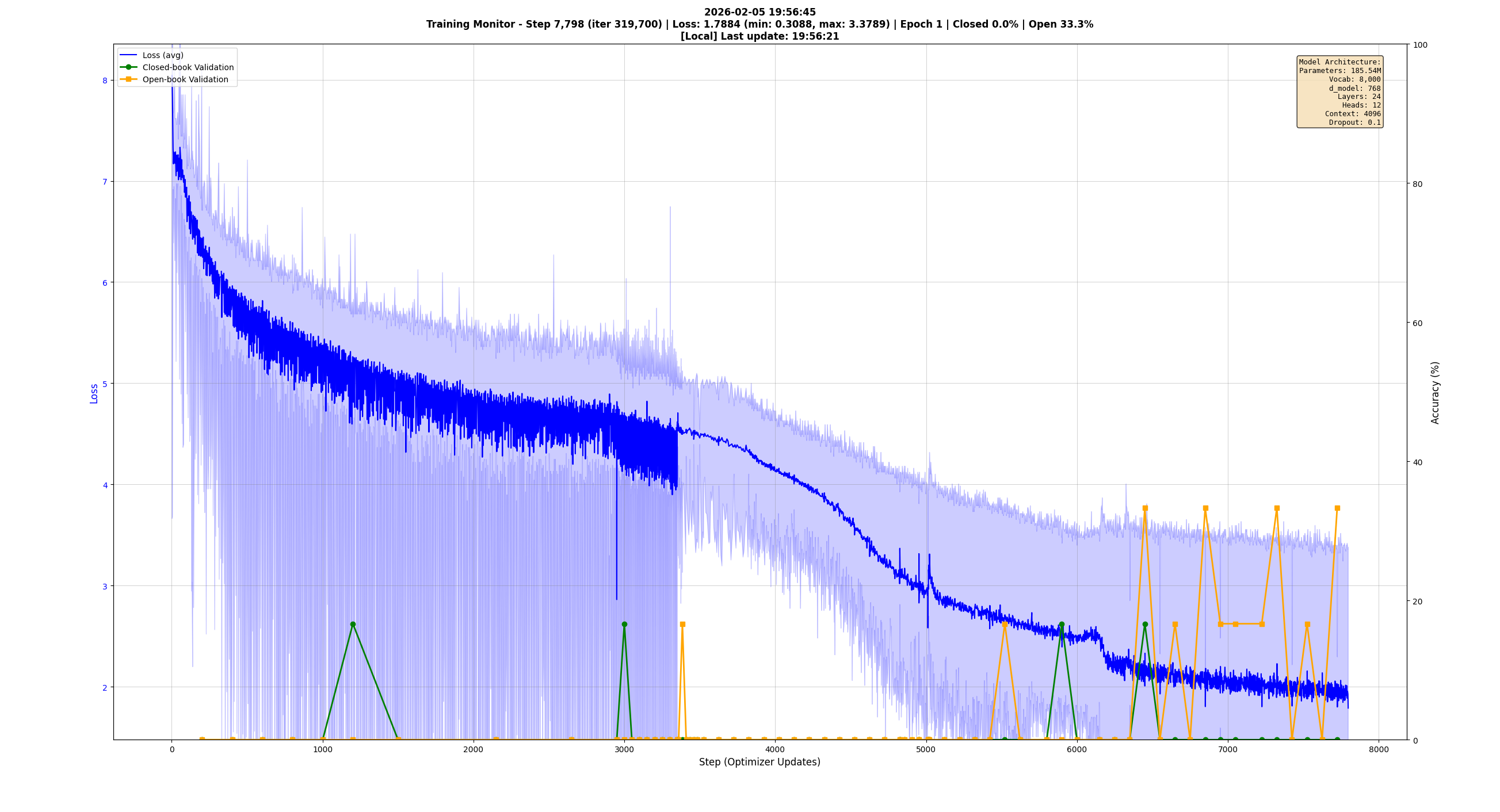

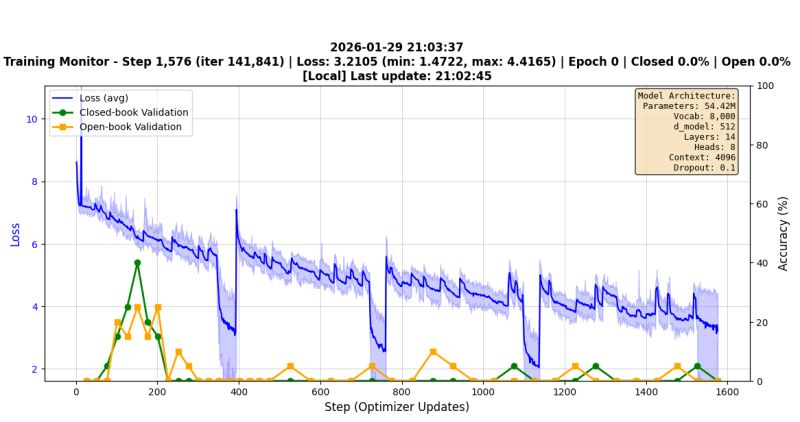

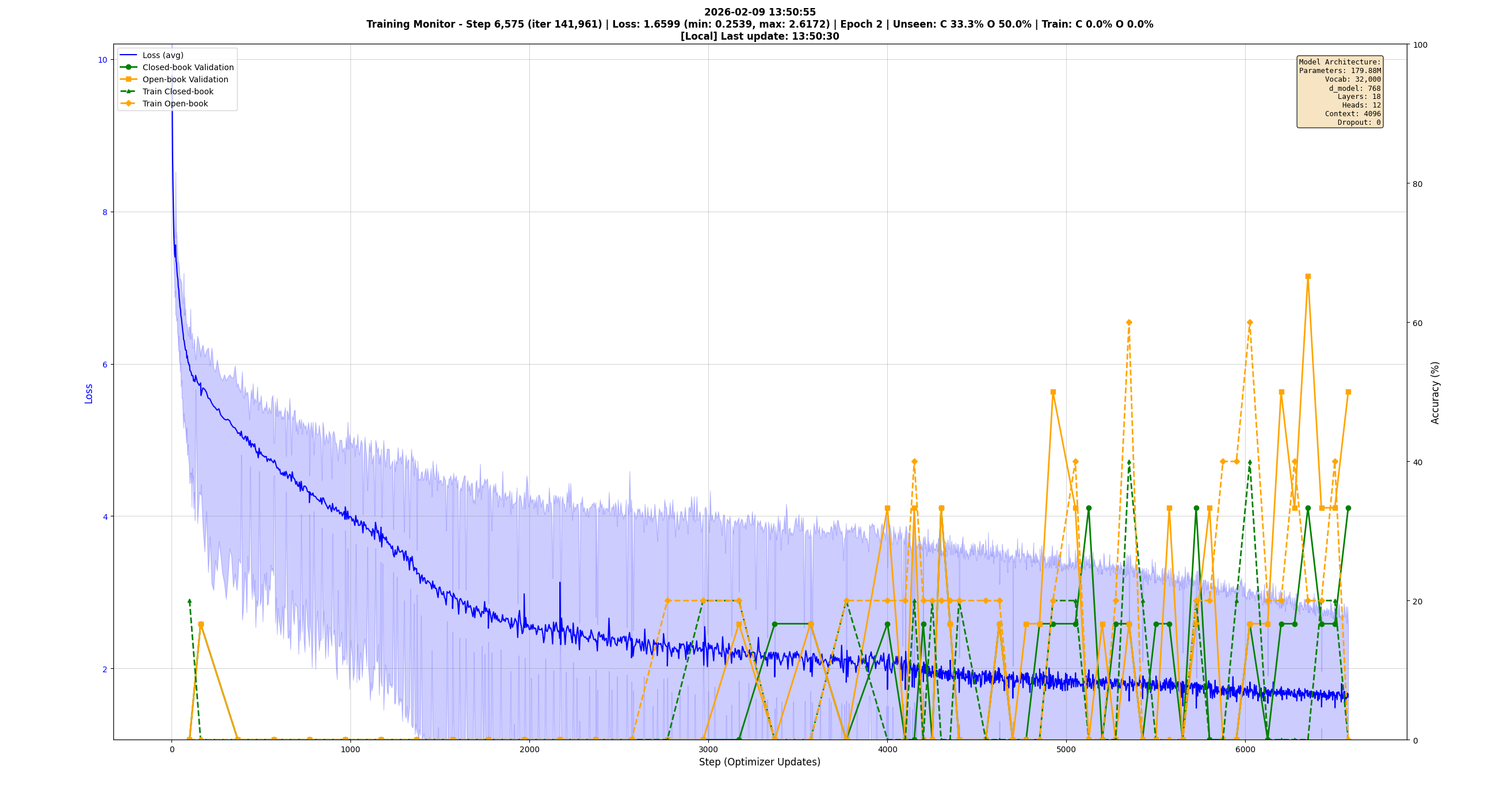

All of these training graphs are generated using customized matplotlib live monitors — an evolution in themselves, iterated over months to show exactly the details that matter so that naming conventions matter less because the critical details are in-picture. The validation metrics use Qwen 3 4B as a judge LLM: Qwen is presented with the source snippet, the question, and the correct answer, then instructed to grade the student model's answer with explanation, outputting a pass or fail that gets parsed out automatically.

The current model takes days to drop a single point of loss. That's the reality of the late stages. The easy gains are long gone.

What This Actually Is

This is not a fine-tuning project. There is no base model being adapted. The model is trained from a randomly initialized state. The tokenizer is custom-trained. The model class is custom-built. The data pipeline is custom-built. The inference loop is custom-built. The validation system with LLM-as-judge is custom-built. The distributed generation infrastructure is custom-built.

35,000 lines of Python. 140 GB of data. 711 commits. One person. One consumer GPU.

This entire project is a personal endeavor. Personal time, personal resources, personal money. It is not connected to any employer past or present.

The entire stack from downloading Wikipedia dumps to a working WW2 chatbot, built from scratch. Not following a tutorial. Not adapting someone else's framework. Solving OOM errors at 1 AM, debugging attention masks at the token level, labeling failed models with honest names, and committing "try 16, try 20, try 18, 16 it is" until the GPU cooperates.

The current model is still training. Still iterating. The workload queue has over 137,000 items lined up for more generation. The commit history says the last change was yesterday.

It's not done. It's never done. That's kind of the point.